- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Indigenous territory and society in the Chicama Valley in the 16th century

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

The Use of Spondylus Shells in Moche Ceremonial Contexts: Why Were They Symbols of Status and Wealth? ...

El Brujo Celebrated International Museum Day with Its Community: A Day of Encounter and Cultural Co-Creation ...

To receive new news.

Por: Jose Ismael Alva Ch

By: Jose Ismael Alva Ch.

Resident Archaeologist at the El Brujo Archaeological Complex

The Spanish invasion provoked profound changes in the social and territorial organization of the Andean world. Upon the establishment the Viceregal government, the encomienda system was instated, through which the colonists benefited from the labor of Indigenous people and relocated the native populations to so-called “reducciones” with the objective of facilitating the collection of tribute and the organization of labor.

The testimonies of the ethnic leaders, or curacas, from the Chicama Valley, recorded in documents written by the Viceregal administration, are an important source of information, telling of multiple aspects of the Native social order and its changes during the early Colonial Period. In the following, we will present some results from studies carried out on this topic in the last decades.

The pre-Colonial Chicama Valley

Located on the present-day North Coast of Peru, the Chicama Valley was recognized by the Spanish soldier Pedro Cieza de León and by the religious figure Antonio Vazquez de Espinoza as one of the largest and most fertile landscapes of the recently conquered region (Cieza de León 1984, p. 207; Vazquez de Espinoza 1948, p. 365). These conditions were generated by human efforts invested several centuries before the construction of irrigation canals that allowed for the expansion of the agricultural area.

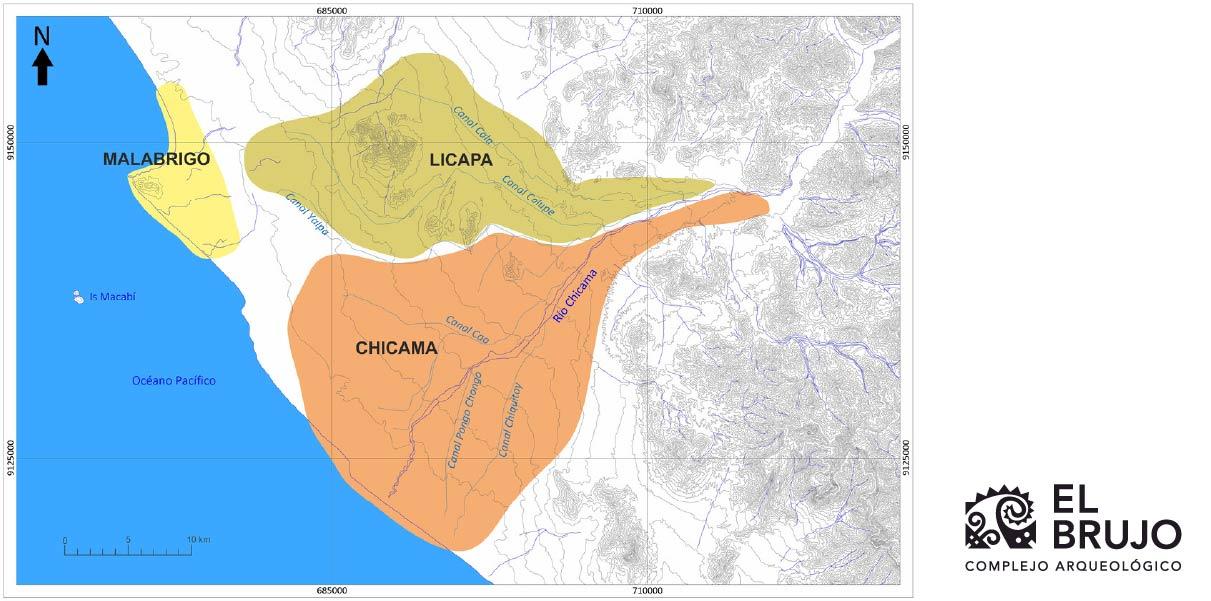

According to Native stories about the valley, up until the start of the Colonial Period, the Chicama lordship existed under the government of Chayguaca, its last lord. This great state was composed of three political units, all of which had their own principal curacas (Hart 1983, p. 289; Netherly 1977, p. 137):

- Chicama: This was the largest of the three. It was located to the South of the town of Chocope, encompassing both sides of the Chicama River up to the location of Sausal to the East.

- Licapa: It was located to the Northeast of Chicama, having as its borders the ancient canal of Yalpa to the South and the Andean foothills to the North.

- Malabrigo: It was located in the northeastern end of the valley, in the modern Puerto de Chicama.

While these political units were connected through the matrimonial alliances of their elite, there was also a hierarchical order to their authorities. Thus, the curacas of Malabrigo rendered service to the curacas of Licapa, and these were at the service of the nobility of Chicama (Hart 1983, p. 290; Ramírez 1995, p. 252).

Figure 1. Map of the distribution of the pre-Hispanic political units of the Chicama Valley at the beginning of the 16th century.

Figure 1. Map of the distribution of the pre-Hispanic political units of the Chicama Valley at the beginning of the 16th century.

Encomiendas, reducciones, and hierarchies

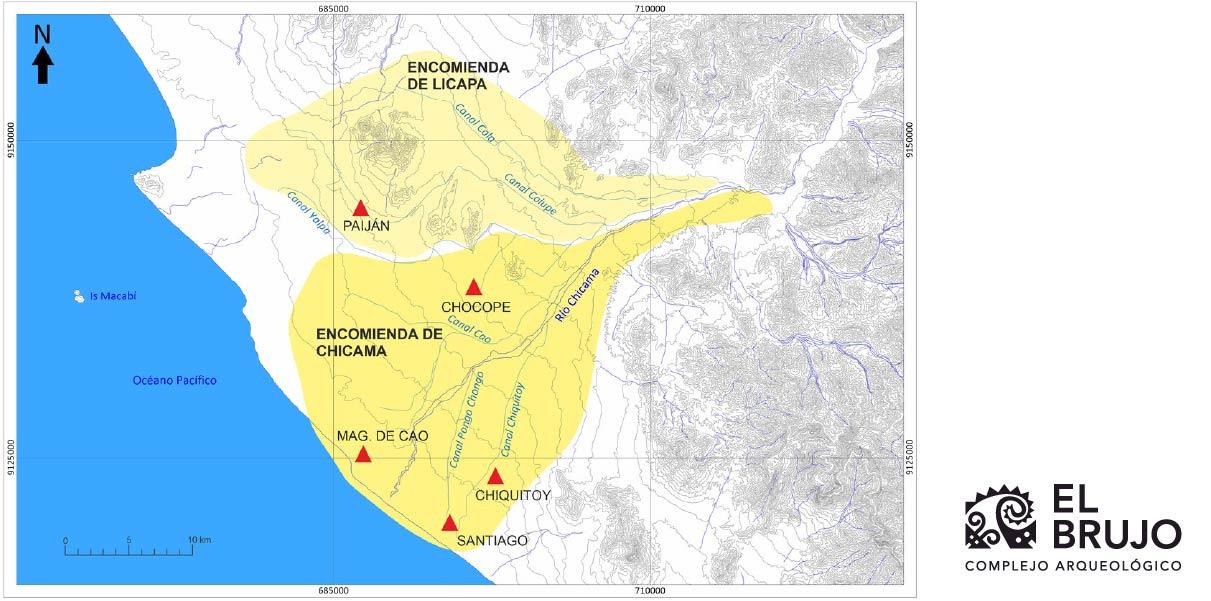

A series of changes came about in the Andean world after the break-up of the social order of Tahuantinsuyu, the deaths caused by illnesses brought by the Europeans, and the imposition of Spanish institutions. In the Chicama Valley, these alterations were marked in the 1560s with the establishment of the encomiendas of Licapa and Chicama, as well as the founding of various reducciones de indios (Indian settlements) in places where there were probably already Native populations and associated irrigation canals.

Ethnohistoric studies indicate that the encomienda of Licapa, given to the Spaniard Franciso de Fuentes Guzmán, had as its pricipal curaca Don Francisco Nuxa, and the town of Paiján was its headquarters and the most notable reducción during the mid-16th century (Hart 1983, p. 305; Ramírez 1995, p. 254; Zevallos Quiñones 1996, p. 308). On the other hand, the encomienda of Chicama, given to Diego de Mora Pizarro, contained at least four reducciones: Chocope, [Magdalena de] Cao, Santiago [de Cao], and Chiquitoy (Hart 1983, p. 299; Netherly 1977, p. 137; Ramírez 1995, p. 260).

During that time period, Indigenous political power within the encomienda of Chicama was reorganized in reference to the Andean principles of duality; it had the river as the geographic division between the two major sectors (North and South). In this manner, in 1568 there were four main curacas installed in complementary and hierarchical positions among themselves (Hart 1983, p. 295). Don Juan de Mora, who upon his baptism took the surname of the Spanish beneficiary of the encomienda, was the principal curaca of the Chicama Valley with his residence in the town of Chocope. Don Alonso Chuchinamo was the other main curaca of this sector and inhabited the town of Cao (or Caux), known later on as Magdalena de Cao. To the South of the Chicama River, Don Pedro Mache was the most renowned principal curaca of the encomienda after Don Juan de Mora, and resided in the town of Santiago de Cao, know previously as Santiago Quechecpa. Finally, there was the curaca Don Gonzalo Supinamu, whose town of residence is unknown (Castañeda Murga & Gálvez Mora 2002, p. 63-64; Hart 1983, p. 299; Netherly 1977, p. 137; Zevallos Quiñones 1992).

Figure 2. Map of the Chicama Valley showing the encomiendas of Licapa (to the North) and Chicama (to the South), as well as the main reducciones, or Indian towns.

Figure 2. Map of the Chicama Valley showing the encomiendas of Licapa (to the North) and Chicama (to the South), as well as the main reducciones, or Indian towns.

Economic activities

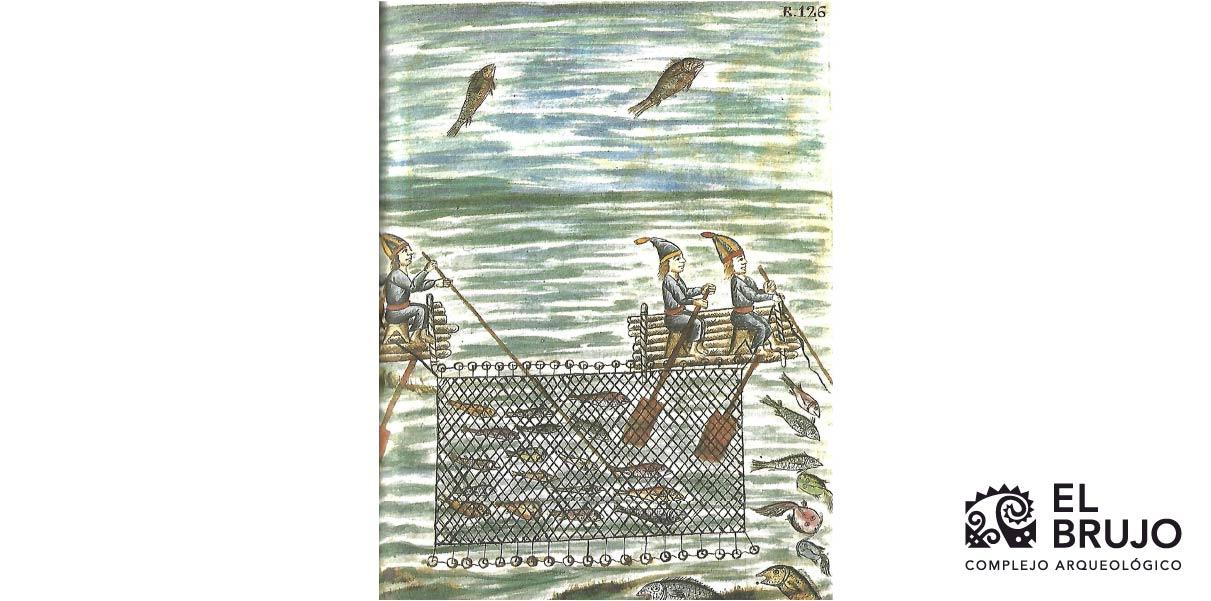

Throughout the 16th century, the Indigenous community of Malabrigo continued carrying out its traditional economic activities such as fishing, salt exploitation, salting of fish, and the exchange of this marine resource for agricultural products, given that they did not possess lands to cultivate. To the South, the reducciones of Cao and Santiago were inhabited by families of rural farmers and presumably also by fisherpeople who took advantage of the ample shoreline. On the other hand, the interior towns such as Chocope were where the farmers lived, who progressively incorporated the mass production of foreign plants such as wheat and, of course, sugar cane.

The hunting of deer, widely represented in Moche ceramics, was done with hunting dogs brought by the Europeans. In this line, the curaca Martin Socnamo testified in 1566 that he owned four dogs for hunting the deer that were found in the agricultural fields. The meat of these animals was part of the sustenance of the families of the valley (Hart 1983, p. 308; Netherly 1977, p. 79).

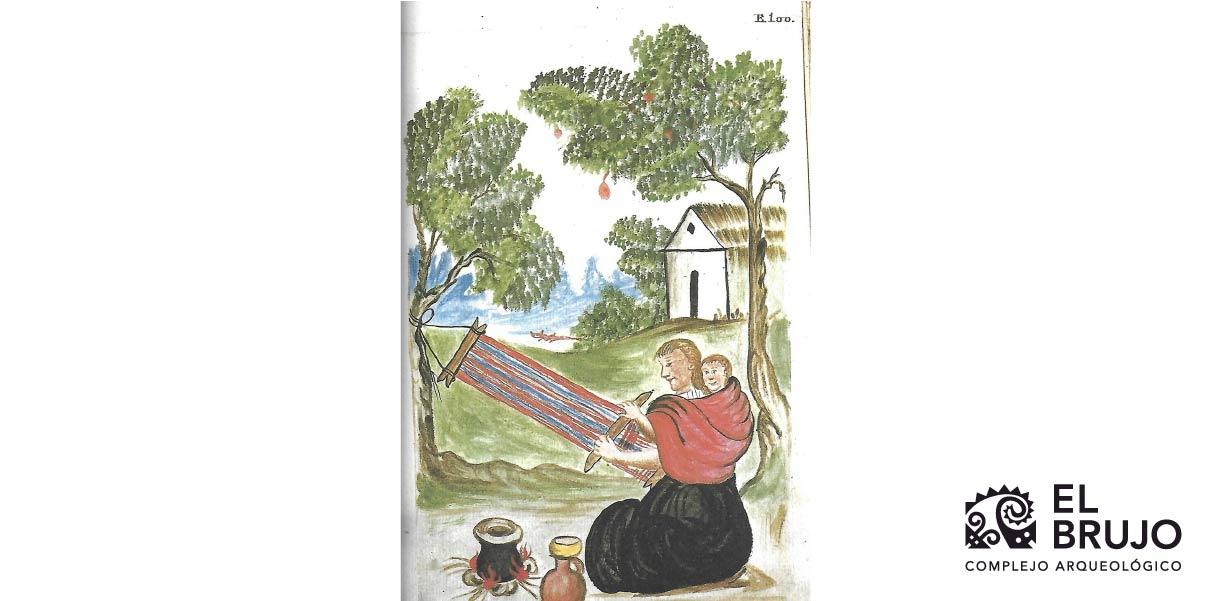

The information written about artisanal activities is scarce; however, archaeological excavations carried out in the ruins of the town of Magdalena de Cao at the El Brujo Archaeological Complex have recorded evidence of Native production of textiles, ceramic vessels, Spondylus and mother-of-pearl beads, and metal artifacts, in large part maintaining their own cultural patterns (Quilter 2020).

Indigenous fishing done with wooden rafts and nets during the 18th century. Drawing published by Bishop Martínez Compañón (Martínez Compañón 1985, f. 126).

Indigenous fishing done with wooden rafts and nets during the 18th century. Drawing published by Bishop Martínez Compañón (Martínez Compañón 1985, f. 126).

Native weaving on a waist loom in the 18th century. Drawing published by Bishop Martínez Compañón (Martínez Compañón 1985, f. 100).

Native weaving on a waist loom in the 18th century. Drawing published by Bishop Martínez Compañón (Martínez Compañón 1985, f. 100).

In summary…

Written records and materials from the early Colonial Period contain much information about the transition from the original ways of life of the peoples of the Andes to the progressive adoption of European models. In the case of the Chicama Valley, Spanish rule left an unerasable mark on the political configuration of the valley. With the passing of the centuries, various colonial reducciones became the capitals of the modern districts of the province of Ascope, where its people are the inheritors of that intricate historical process of the region and of Peru.

Researchers , outstanding news